The Fool's Journey

The Fool's Journey

THE FOOL’S JOURNEY | QUARANTA | SPRING MAPS | THE LOS ANGELES SERIES | LOST PATTERNS | MERCURY | UNTITLED SERIES | LANDSCAPES | FLOWERS, ALWAYS

“Each painting is its own unique drama and reminds us that the past and present fuse together as we gain knowledge in our own journey.” — Susan Lizotte

Susan Lizotte’s Oracular Neo-Medievalism

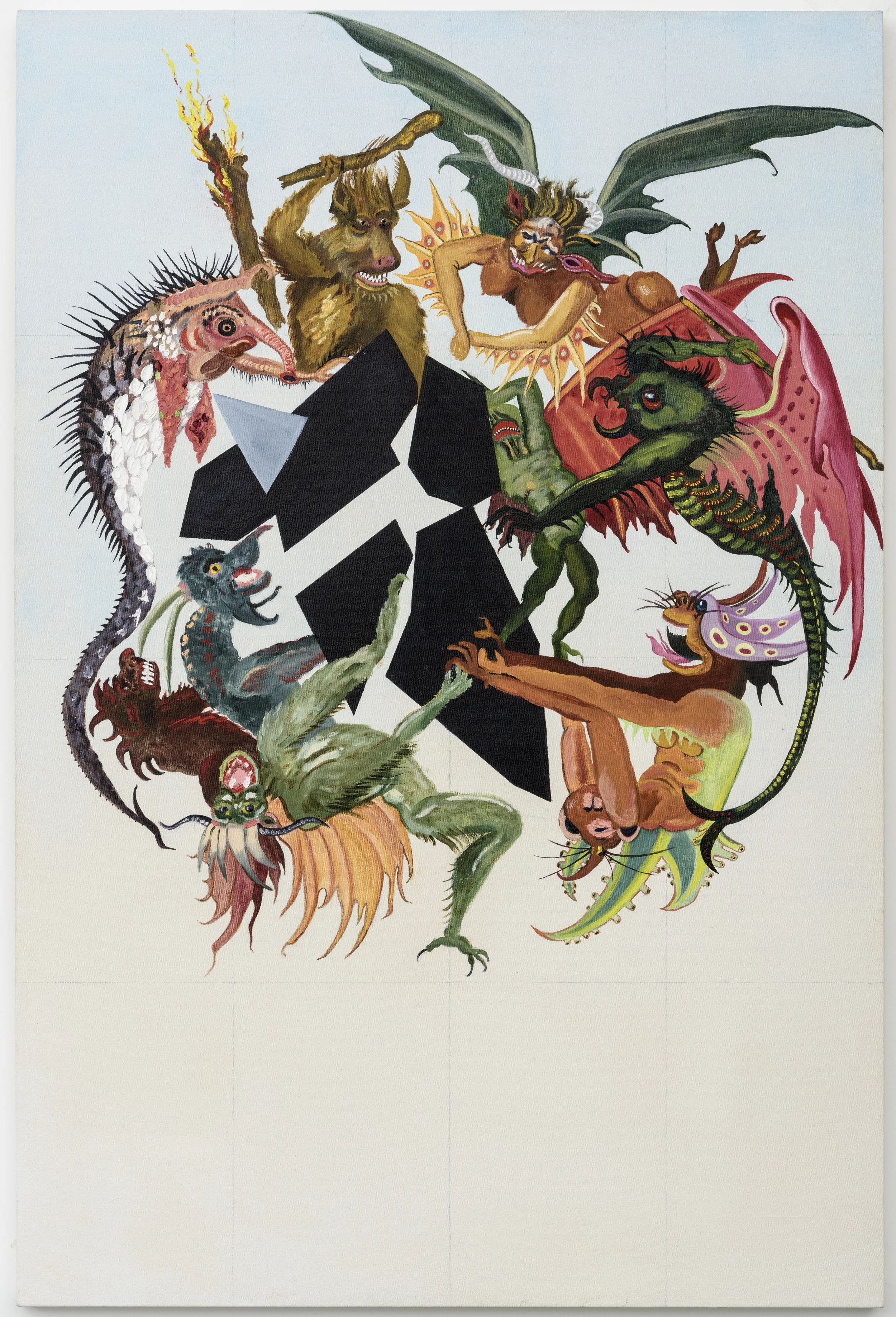

“Tarot and dreams are two dialects in the language of the soul,” writes noted tarotist Philippe St. Genoux — but to that we ought to add a third, more powerful dialect: art. In its most expansive forms, art contains both dreams and divination, along with humanity’s innumerable further facets of mystery, time, psyche, soul, and experience. Art helps us navigate our fear of the unknown, find our place in the world, bring order to the chaotic and invisible forces of nature, and give a shape to history and meaning to life events. Arguably, so does Tarot. So when a contemporary Neo-Medievalist painter like Susan Lizotte wanted a visual framework to express our fraught relationship to the volatile, conflicted, violent, promising, menacing, magical times we are currently living through, the iconic 1491 Sola Busca tarot — a deck initially commissioned as a work of art whose legend has only grown over the centuries — caught her attention.

The Fool’s Journey series speaks to Lizotte’s cultural revisitation in form and narrative, first and foremost by grounding its aesthetic in the corresponding art historical one. The idea — one that has inspired Lizotte’s work for years — is that we live in a time with echoes of the Middle Ages in our wars and disease, power struggles and ignorance, scientific advances and artistic innovations; why not therefore make art that channels that energy in its style as it seeks to message its subject matter. In her previous series, Lizotte has explored ancient maps of war and plague in Europe, legends of ocean-going princely crusaders, and the sacred architecture of worship and of science. In her new tarot-based paintings, Lizotte harnesses this same visual language, for consistent reasons, to explore her motif with the most personal, emotional, relatable storylines to date — our own.

These cards follow the spiritual travels from the innocent state of The Fool to the knowing attainment of The World; this is also the story of humanity's evolution toward enlightenment. But crucially, it further forms the armature for an individual’s own unique path toward their destiny and their truest self. Heady material for what started out as a card game, but the perfect subject matter for art to take on. Tarot — like art — has the power to communicate multiple stories and meanings, even paradoxical ones, simultaneously; both are also malleable to the circumstances of context. Cards convey meaning in large part through the other ones around them and their own physical placement and orientation, just like the effect of curation on paintings. To add to the arcane adventure, cards have counterintuitive meanings — Death might foretell not an ending but a new beginning, the Fool might be the holiest soul, the Philosopher might be getting into trouble with alchemy; the Hanged Man, however, is almost always less than ideal.

The Sola Busca is a brilliant partner for Lizotte in this historical engagement — with its colorful procession of Greco-Roman characters, 15th-century armor and robes, musical instruments, flags, shields, torches and menagerie of symbolic creatures of the land, sea, and air, as well as its penchant for bright, eccentric color-blocking and stylized anatomy reminiscent of painters like Masaccio, Mantegna, Piero della Francesca, and Filippo Lippi. She shares their love for figures of noble yet brutish physiognomy and frieze-like bearing, their romantic and idyllic or perhaps wasted landscapes, motifs of royalty, religion, philosophy, and war — all inflected with the quasi-feral noirish folklore of the Medieval times at the cusp of the Renaissance. Lizotte is right, there’s a lot about the dawn of the 16th century that reminds us of today.

To the degree that much of the series’ power comes from her overt aesthetic engagement, all of this is particularly suited to Lizotte’s established style of muscular allegorical narrative scenes, to her maps of disease and dragon-slaying, archetypes and legends, sea creatures and oracles, temple architecture and wild meadows, as well as her aesthetic of chunky, sensual, gestural, and schematic figures rife with geopolitical undertones. But perhaps what distinguishes Lizotte from her art historical ancestors, is her embrace of the heroic individual story as a synecdoche for humanity’s universal, ever-present struggles. Each painting — each card — performs its role in our own uniquely encoded passion plays, intended to guide our individual journeys, remaining sensitive to intuition, and aware that no matter the magic, the ultimate answers are always already inside each of us, if we know how to look for them.

— Shana Nys Dambrot

Los Angeles, 2023

The Fool’s Journey is a tarot card painting series based on the Sola Busca deck, which is the earliest illustrated complete tarot card deck made in 1491. Initially used as a card game called Tarocchi, tarot has evolved over the years into a divination tool. Tarot is ingenious for the ability to convey manifold meanings ascribed to each card and also convey alternative meanings if the card is presented to the viewer right side up or up side down. The cards have different meanings depending on which cards surround them. The Fool is the first and unnumbered card in the deck, the Fool represents the metaphor for our life journey and all of the stages of life with its hazards and pains, as well as the growth and development from birth/innocence into a fully realized spiritual and physical being. Each painting is its own unique drama and reminds us that the past and present fuse together as we gain knowledge in our own journey. Looking to the metaphysical to find our place in the universe is an invitation with tarot cards into a game of high imagination to try and decode secret meanings and make new self discoveries.

— Susan Lizotte

Quaranta

Quaranta

THE FOOL’S JOURNEY | QUARANTA | SPRING MAPS | THE LOS ANGELES SERIES | LOST PATTERNS | MERCURY | UNTITLED SERIES | LANDSCAPES | FLOWERS, ALWAYS

Literally these are my Quarantine paintings, 23 paintings created in 40 days. Looking more closely at everything surrounding me brought fresh views of my native city, celebrating the beauty of Los Angeles and spotlighting my favorite places.

Quaranta is from the Latin “quadraginta” and the Italian “quaranta”, both meaning 40. It’s first known use was in the 14th century during the Black Plague of 1347.

— Susan Lizotte

Spring Maps

Spring Maps

THE FOOL’S JOURNEY | QUARANTA | SPRING MAPS | THE LOS ANGELES SERIES | LOST PATTERNS | MERCURY | UNTITLED SERIES | LANDSCAPES | FLOWERS, ALWAYS

“The organic contours of geological borders are at odds with the clunky, arbitrary nature of state and national borders, revealing the latter as illusions in the same way as such borders are equally irrelevant to the virus.”

Susan Lizotte: Maps of an Uncertain Spring

Humans make maps to codify what we discover about the world, and to chronicle how we figure it out. As knowledge accumulates, cartographies shift, contours expand and elongate, borders are created and blurred and redrawn, horizons are surpassed, oceans crossed, and mountains measured. The unknown evolves in fits and starts toward an elusive total understanding. But how do we map an invisible terrain? How do we overlay what we see of the world with what we sense of it in our souls?

Lizotte’s Spring Map paintings have been directly inspired by the pandemic and its prolonged quarantine. Returning to years of earlier research into 14th century history and visual culture, Lizotte’s collation of the Covid-19 experience with the Plague of the Black Death begins, perfectly, with their maps. The series keystone work, Mappa Mundi, takes inspiration from Martin Waldseemuller’s 1507 map of the globe — a masterwork made at a time when the urge to explore a planet still all but unknown to Europeans really caught fire, and the first known map to name America. As Europeans spread out across the globe and celebrated their “discoveries,” they also acted as a veritable army of disease vectors, ironically bringing death with them everywhere in their quest to shine a light.

Building her version of this iconic map from a grid of 12 canvases serves to underscore the present day condition of lockdown, separation, isolation, and mistrust — neighbor from neighbor, nation from nation. At the same time, across the entire series actually, her use of old-time materials and mediums like sheepskin parchment, thick oil paint, walnut ink in fountain pens, and hematite crayon serve to tether the narrative to para-Columbian geopolitical events. The dynamic of authenticity and experimentation animates the entire portfolio with a liminal, non-linear strangeness that speaks to the distance between what we knew about the world back then and what we have since come to learn, and perhaps already forgotten.

Much as a Spring of uncertainty and lockdown gave way to a Summer of dismay and frustration, and on the cusp of an Autumn and Winter of madness and discontent, with perhaps a distant new Spring almost in reach, the explorers and map-makers pressed forward into absolutely unknown regions. Their first impressions often proved inaccurate, and look bizarre to us now, like distortions or outright inventions, or stormy places marked “here be dragons.” In other words, they look like how we currently feel.

The palette — pale parchment yellow, radiant aquamarine and emerald, fleshy, fruit roses and reds, lovely warm raspberry, and cool olive — is an evocation of Spring with its fecundity and metaphor-friendly stance of hope. The paint is thickly applied, offering topographical and emotional texture and enacting small passages of abstraction within cartographic regulations. The organic contours of geological borders are at odds with the clunky, arbitrary nature of state and national borders, revealing the latter as illusions in the same way as such borders are equally irrelevant to the virus.

The lands, though redolent with flowers both in bloom and in decay, are largely absent of figures. This is both a literal reference to the absence of society during quarantine, as well as the invisible nature of the virus itself. It is also a way of holding space for her abstractionist impulse, creating opportunities for generative, evocative nature to reclaim the planet we are parsing. As we proceed from a recognition of Italy, the United States, Great Britain, the South Pole and so on to an increasingly abstract environment, orientation within the terrestrial field gives way to the more amorphous territory of ourselves. We will have to relearn the world outside when this is over — but it’s the world inside that we are exploring now, and in these paintings being mapped out in all its unknown terror, pleasure and promise.

— Shana Nys Dambrot

Los Angeles, 2020

My Spring Map paintings are inspired by the quarantine of Covid-19. They are a means to juxtapose the 14th century plague with the 21st century pandemic. Using Renaissance maps to speak to the spread of disease felt fitting as a starting point for finding our place in a new unknown world. The geography of these old maps is inaccurate, strange and unsettling. I’m using this inaccuracy deliberately to convey confusion and disorientation.

My Mappa Mundi takes inspiration from Martin Waldseemuller’s 1507 map of the globe (the first map to name “America”). Creating the painting out of twelve canvases (each measure eighteen by twenty four inches), using the identical measurements as the 1507 map, seems the perfect metaphor for how the entire globe has been shattered by Covid-19, nation’s shutting borders and residents under lockdown, all separated.

Covid-19 has been largely an unseen, silent killer, almost an abstraction. Victims have been obscured by medical equipment and by quarantine. The map paintings use paint as an abstraction and nature as our symbol of hope going forward. The use of boundaries is my metaphor for boundaries between the virus and humanity. Each line is deliberately wavy, deliberately handmade as it moves through time and space, my personal framing of the pandemic. The colors are a nod to spring and regeneration, including flowers in states of full blossom as well as decay. The paintings are my thoughts and dreams of our place in time.

— Susan Lizotte

The Los Angeles Series

The Los Angeles Series

THE FOOL’S JOURNEY | QUARANTA | SPRING MAPS | THE LOS ANGELES SERIES | LOST PATTERNS | MERCURY | UNTITLED SERIES | LANDSCAPES | FLOWERS, ALWAYS

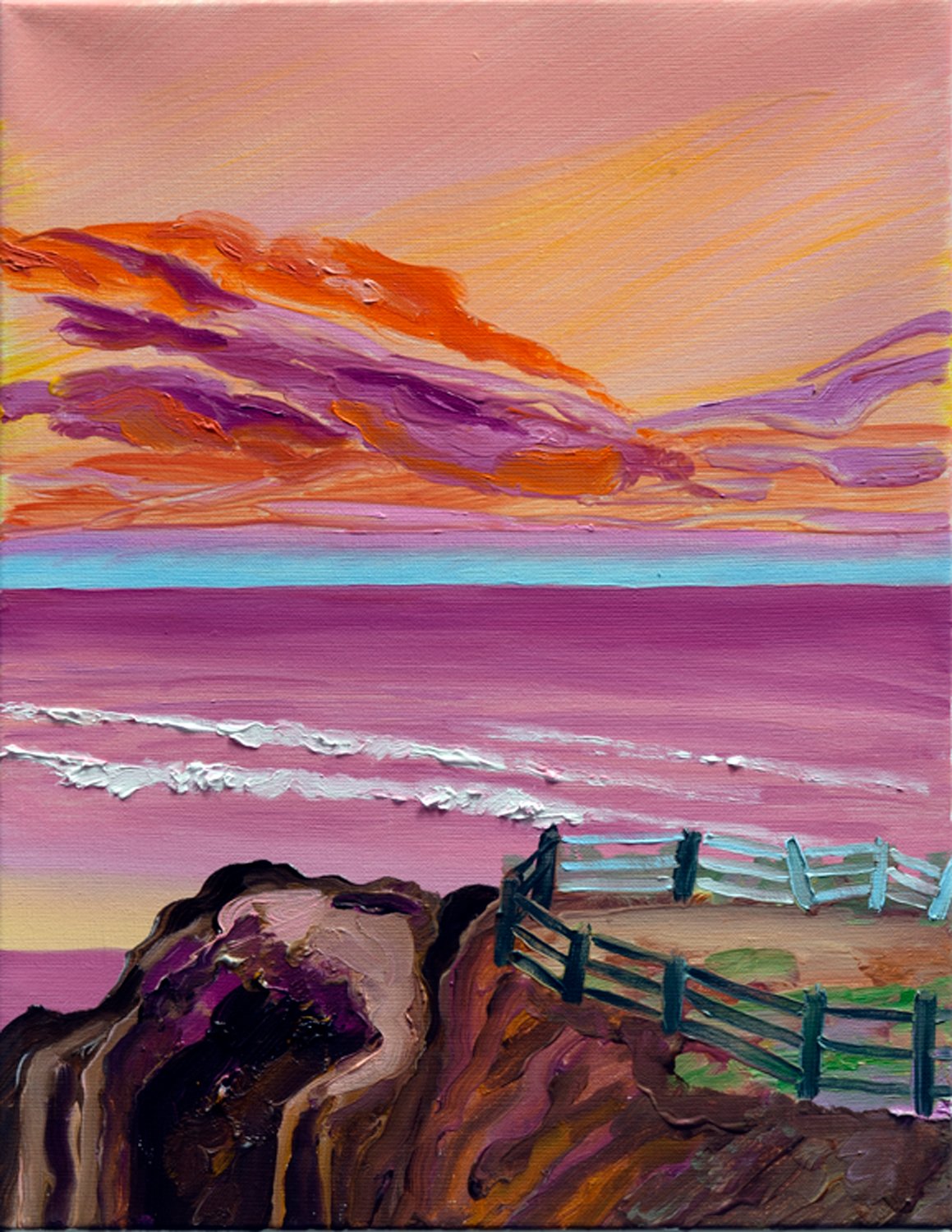

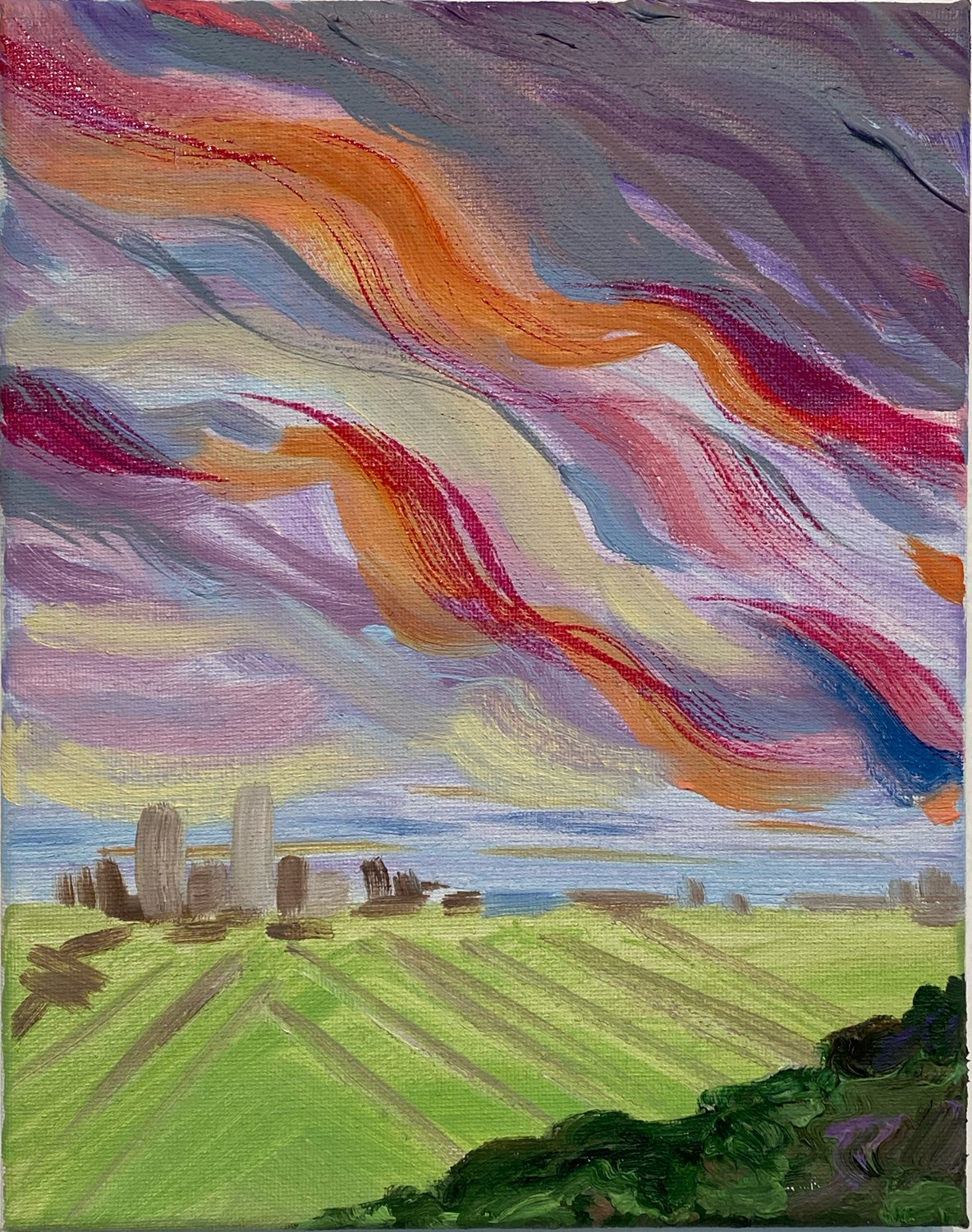

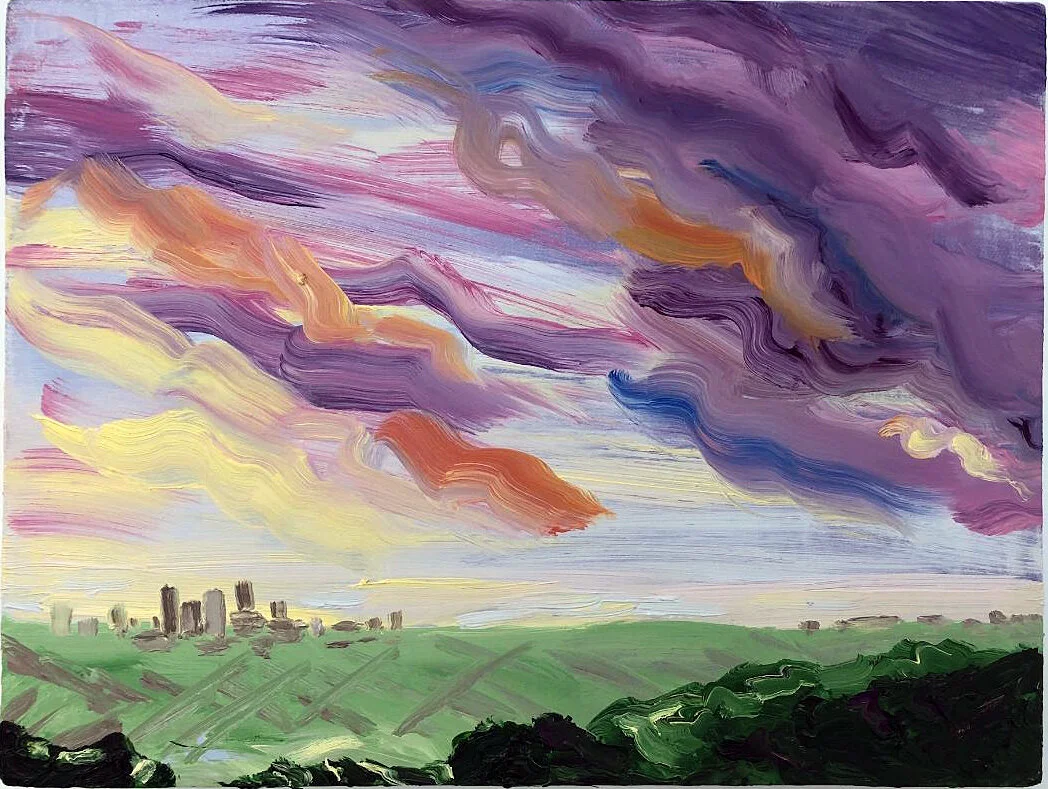

The duality of life in Los Angeles is depicted in the painting series “Los Angeles: A Different Narrative”. The paintings show a collection of private and public views, both beautiful and destructive, that make up the urban landscape crisscrossing Los Angeles.

Joan Didion summed up life in Los Angeles “the unpredictability of the Santa Ana winds affect the entire quality of life in Los Angeles, accentuate its impermanence, its unreliability. The wind shows us how close to the edge we are.” These paintings show our fragility and our resilience.

— Susan Lizotte

Please contact us if you’d like to view the complete collection.

The Los Angeles Series

Shana Nys Dambrot, Los Angeles, 2019

Reality in Los Angeles is weird enough already, before an artist even has a chance to intervene. In L.A. what might be most people’s idea of zany is our baseline normal. This goes for the residents and the landscape, the architecture and the cars, the natural light and the preternatural climate. For a painter like Susan Lizotte, it’s irresistible. She loves L.A. in only the way a prodigal transplant can. Born here but raised elsewhere into her teens, Lizotte’s return was infused with a heightened sense of attentiveness and preceded by both private and cultural fantasies. Her eyes grew wide as she took it in, and they’ve stayed that way.

Previous painting series have dealt with more codified themes, from war and disease in medieval history to personal family emblems and secrets. Through it all, Lizotte has developed a kind of post-folk visual vocabulary in which gestural impasto is tethered to flawless grounds, anatomy and geometry are rendered as malleable, and color is in no way subservient to form. In her newest works, she deploys the cargo of her heavy brushes not in pursuit of dreams and myths, but rather to an embrace of the world around her -- which as mentioned above, was plenty strange enough as she found it.

For her landscapes and architectural elements, she culls from an expansive collection of views and vignettes across the richly variable and frequently surreal sights of the city. L.A. is a major urban territory, but with no single center; between its several hubs lie stretches of unpredictable semi-urban eccentricity and majestic incursions of nature. From the mountains to the ocean, canyons to canals, random gardens, bedraggled landmarks, beacons of tourism, redevelopment zones, and inexplicable blight. “When the wildfires are burning,” says Lizotte, “there are usually exquisite sunsets. Sometimes the horrifying experience can yield the sublime.”

Her rather epic paintings of both the Griffith Observatory and LACMA on fire refers to the precariousness of life in our geography. But like her fire-threatened Hollywood sign, it’s also riffing on a proper art historical meme, with Ed Ruscha, David LaChapelle, and Carlos Almaraz all playing with the idea of natural disaster and urban landmarks. A companion to the LACMA painting, Lizotte has created a portrait-like diptych of a single lamp-post from “Urban Light” as it sags. Melted like a great dropping flower, or curling upon itself, serpentine, a witness to the flames, is it too much to say that lamp-post is us, an avatar of humanity present in the landscape? Like the endless selfies taken at “Urban Light,” the scenes in Lizotte’s compositions capture personal experiences unfolding in shared spaces. After all, in Los Angeles, every experience is always both private and public.

From her regal estate-style painting of the Griffith Observatory crowned in flames, to a hedged-in sculpture garden with statuesque works that stand strange and strident like the “Demoiselles d’Avignon,” to the pastoral bus stop on Sunset and Rodeo, that gleams like an Impressionist cottage, Lizotte’s inspiration for the new works may be the real world, but her style remains assertively painterly. For her, illusion and realism are not only beside the point, but somewhat suspect, and anyway unnecessary for imparting a viscerally true sense of this place. Her topographical pigments and flickering, ragged edges -- that’s Los Angeles. As Lizotte sensed from afar and then proved up close, this beautiful city is mostly made of ragged edges. The thing is, she likes it that way, and she builds her paintings of it accordingly.

Gallery Lost Patterns

Gallery Lost Patterns

THE FOOL’S JOURNEY | QUARANTA | SPRING MAPS | THE LOS ANGELES SERIES | LOST PATTERNS | MERCURY | UNTITLED SERIES | LANDSCAPES | FLOWERS, ALWAYS

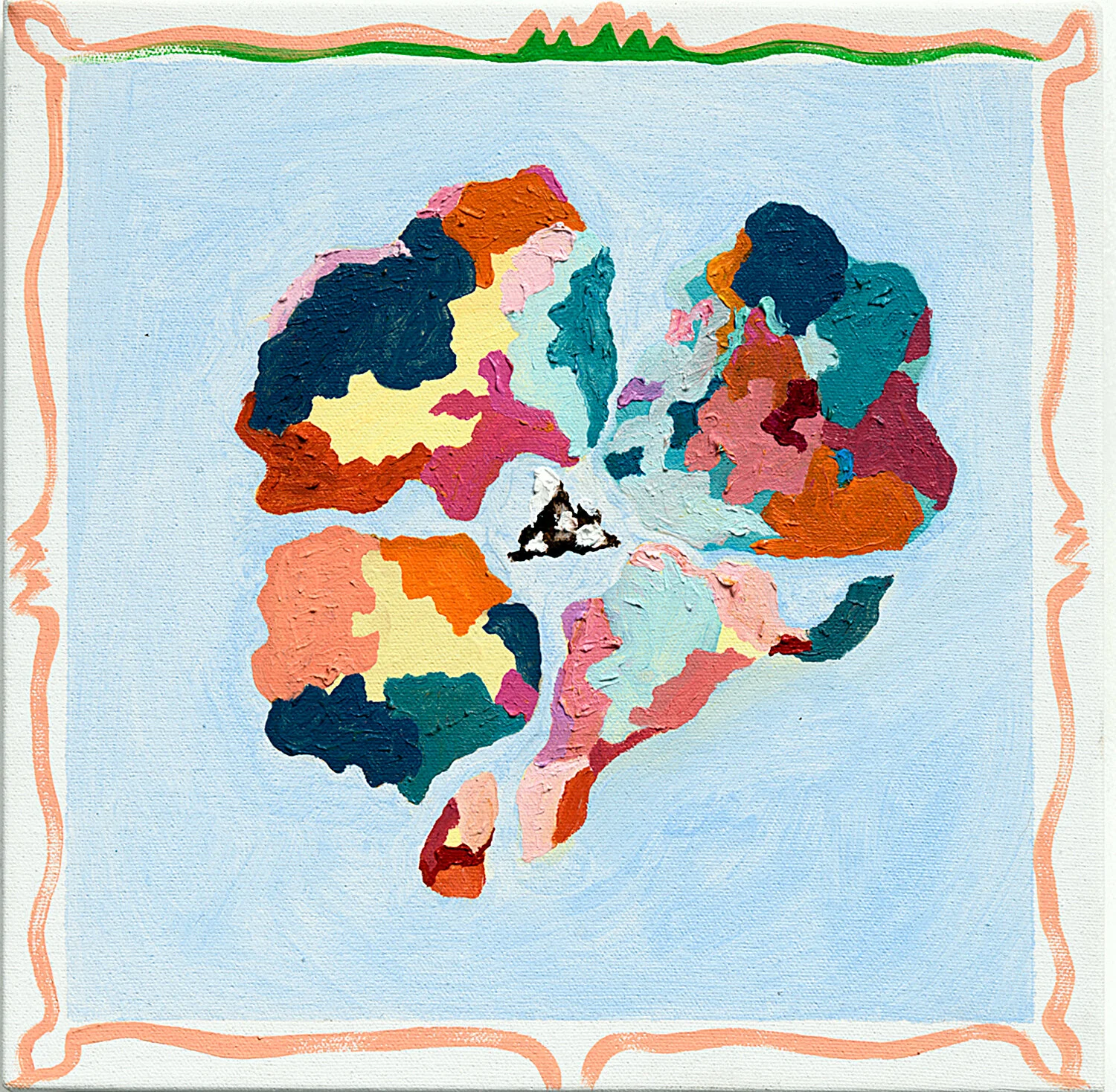

These paintings are inspired by lost patterns and lost underdrawings revealed by scientist Pascal Cotte's digital multi spectral camera analysis of Leonardo Da Vinci's paintings Mona Lisa and Lady with an Ermine. The lost markings mirror lost history to me and the fragility of our own human existence. Change and it's inevitability ebbs and flows around us making things invisible which were previously visible.

— Susan Lizotte

Please contact us if you’d like to view the complete collection.

Gallery Mercury

Gallery Mercury

THE FOOL’S JOURNEY | QUARANTA | SPRING MAPS | THE LOS ANGELES SERIES | LOST PATTERNS | MERCURY | UNTITLED SERIES | LANDSCAPES | FLOWERS, ALWAYS

I'm exploring in paint the issues of abuse of power, control, image production, information, mercury and mythology. I am concerned with the abuses of the medical establishment and the government. The misuse of mercury, the element, began at the end of the 15th century. Its misuse continues to this day and is closely linked to the rise of Autism, although hotly debated. The paintings seek to address images created to further an agenda, used by those in power. The paintings are flawed or broken to show both seen and unseen. Architecture is intended to evoke power as a symbol, a place where everyday decisions have the potential to inflict terror on society. With a range of stylistic approaches and methodologies I'm examining the nature of investigation, via painting, in relation to art history, as a reflection of the myriad journeys of the Mind.

— Susan Lizotte

Please contact us if you’d like to view the complete collection.

Susan Lizotte: Blood & Treasure

Shana Nys Dambrot, Los Angeles 2015

In her latest body of work, the curious and expansive series Mercury, painter Susan Lizotte both mines and mimics history to construct a poignant and eccentric allegory for the present day. She marries a haute-naif aesthetic of thick lines, blocky color, proto-Cubist mannerism, and collapsed perspective with a visual lexicon of knights errants and dogged explorers, sea monsters and tall ships, architectural ruins and sketchy outlines of uncharted territories. All of which serves to reconstruct an alternative narrative of the New World and certain rather salacious and cynical, yet consistently under-reported, consequences of its “discovery” for the Old World -- and how those forces and effects continue to shape the world today. Ultimately an indictment of power and its abuses, Mercury traces the roots of medical, industrial, environmental, and commercial misbehavior that have been shaping life on earth for 500 years and counting. And it uses art history to do it.

In both style and content, Lizotte’s modern medievalism prefigures a new dark age, as the 16th century dawns anew at the start of the 21st. Her striking, emotional rendering of both figure and ground wavers between her premise’s representational imperatives and a gravitational pull toward abstraction that fittingly has more in common with pre-Raphaelite awkwardness than contemporary gestural expression. Her tertiary palette also seems culled from another era, one of parchment and velvet, sea foam and starry skies. Although Lizotte engages this art historical motif to depict geopolitical events from the same era her pointed content references, this gestalt is punctuated by compositional incursions large and small in the form of splashes of neon color, faintly pulsing grids in a dusky sky, and outright anachronisms like spray paint and text that slam into the present day at crucial moments, injecting both chemical clarity and disorienting ambiguity into the conversation.

Mercury in ancient mythology was the messenger god, conduit to the underworld, patron of thieves and commerce. It is also a metallic element that is beautiful and poisonous, widely used in early modern medicine, until its nefarious properties were observed. After that it was still used -- just mostly on the unsuspecting. In Lizotte’s project, she focuses on its use in Europe after 1500, specifically to treat the particularly virulent strain of syphilis that Columbus and those who came after him managed to bring back to Europe along with their treasure and appetite for glory. This story of karma, irony, disease, greed, racism, fear, technology, and government overreach took place in an age where magic still held sway but humans were increasingly looking to science for answers. In regarding this particular chapter of ancient history, Lizotte cannot help but see the world around her now. Far East, Near East, Middle East. Colonialism, conquest, hubris. Church, state, commerce. Environment, industry, religion. Mercury is a story that continues to unfold across centuries of Western history, its players perennially locked in an intercontinental Game of Thrones complete with kings, pawns, dragons, sex, death, and pirate gold.

Gallery Untitled Series

Gallery Untitled Series

THE FOOL’S JOURNEY | QUARANTA | SPRING MAPS | THE LOS ANGELES SERIES | LOST PATTERNS | MERCURY | UNTITLED SERIES | LANDSCAPES | FLOWERS, ALWAYS

“The seasons and the passing of time resonated for me to represent the cyclical nature of birth, life and death. Fragility, vulnerability and strength in the midst of overwhelming emotional turmoil are elements to celebrate.”

— Susan Lizotte

Please contact us if you’d like to view the complete collection.

A Serene and Ghostly Presence: The Quietly Enigmatic Paintings of Susan Lizotte

by Eve Wood

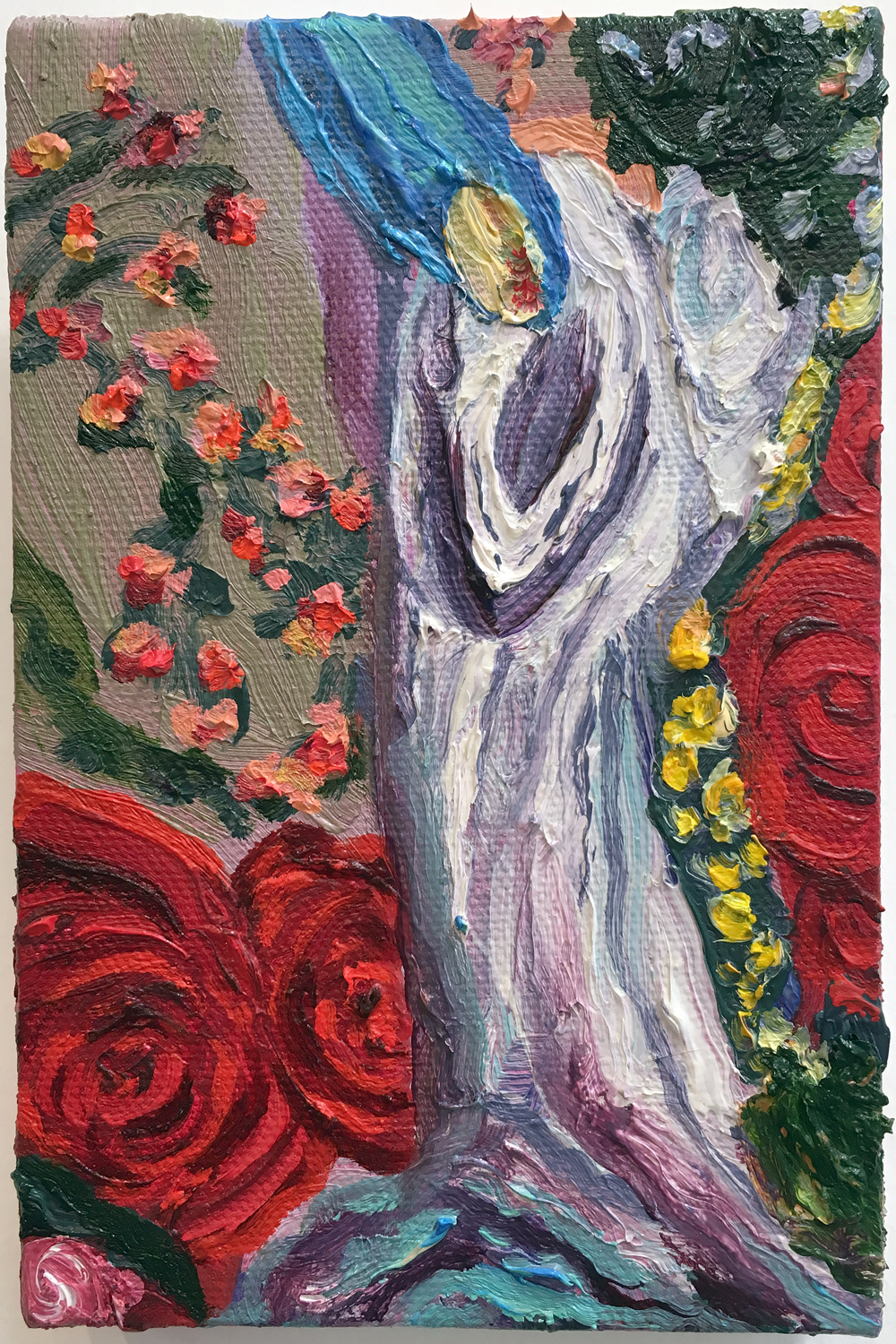

Tennessee Williams said in his famous play Camino Real that “the violets in the mountains have broken the rocks,” meaning that something fragile and delicate can overtake even the harshest conditions, or soften the hardest heart. Susan Lizotte's painting's, mostly oil on canvas and wood, comprise a set of images that deal, both directly or indirectly with issues of mortality, love and loss.

Lizotte's adopted father passed in 2017 and these paintings are a visual response to loss, and are at once bold, lush and expressive in the very best sense of the word. They utilize flowers as symbols of loss but also as emblems of regeneration and rebirth. Artists like Marc Chagall and Wassily Kandinsky come to mind as these artists all utilize motifs of flowers and bright expansive fields of color to represent a larger more complex system of loss that ultimately includes love, forgiveness and celebration. As with these artists, Lizotte's work is also imbued with a sense of mystery and the fact all of the paintings are untitled adds to the sense of the miraculous having already happened, yet still continuing to blossom. They also are suggestive of a variety of literary references, not only Williams but the image of the wayward soul of Shakespeare's Ophelia comes to mind:

Her clothes spread wide;

And, mermaid-like, awhile they bore her up:

Which time she chanted snatches of old tunes;

As one incapable of her own distress,

Or like a creature native and indued

Unto that element: but long it could not be

Till that her garments, heavy with her drink,

Pull'd the poor wretch from her melodious buy

To muddy death.

The fragments of disassociative images in Lizotte's paintings all suggest the female body, or parts of it seen at various intervals much like Ophelia sinking slowly into her watery grave, her body surrounded by the flowers she picked with her own hands. Though most of the paintings contain iconographic references to flowers, the images also contain more personal references as in one painting where a woman's dress appears to be floating in a vaguely disquieting field of poppies. Again, this is reminiscent of Ophelia, the dress with its ghostly presence, as a milky confluence of blues, grays and pinks dominate the center of the image, yet strangely, the dress is empty, or rather filled with the weight of possibility, fluid and changing, a hopefullness, a means by which the experience of tragedy, of loss might be transformed into a more positive association. The flowers in this image also reflect movement, a garland of blooms skirting the dress as though lifting it up and onto the wind. Giant blood red poppies punctuate the surrounding space, in a kind of menacing gesture that seems to balance the quietude of the floating dress.

These paintings are as much about what is not there as they are about what is keenly felt and experienced. Nowhere is this more apparent than in the loosely enigmatic image of what appears to be an arm or a leg, again seen to be floating disembodied through space. The appendage is covered ironically with a sheer fabric that could be a piece from a wedding dress or a wayward bit of lace. This sense of the unseen being seen and experienced by both the viewer and the artist together is also another underlying theme in the show, and again, as in other images from Lizotte's series, the central figure is surrounded on all sides by flowers; yet the painting is strangely interrupted by an encroaching black mass which could be representative of the weight of the past, unresolved memories or feelings yet to come. If one were to read this work metaphorically, you could argue that the painting is divided between two poles of experience, the burgeoning light and color on the left hand side of the canvas versus the complete absorption and negation of experience on the right.

This tentative balance between opposites– color versus no color, light versus dark, implied narrative versus complete abstraction is what makes these paintings powerful and engaging. Also, each of the works has a central image that is mostly recognizable whether it be a dress, a sleeve or a darkly shrouded encroaching mass of darkness that keeps us continually engaged as viewers. It's a discernible tension that exists within each of these images separately yet also operates on a larger scale collectively as an overall theme of opposition. Lizotte's narratives are not easily discerned, but are hard won like all good things. They keep us invested and looking deeper.

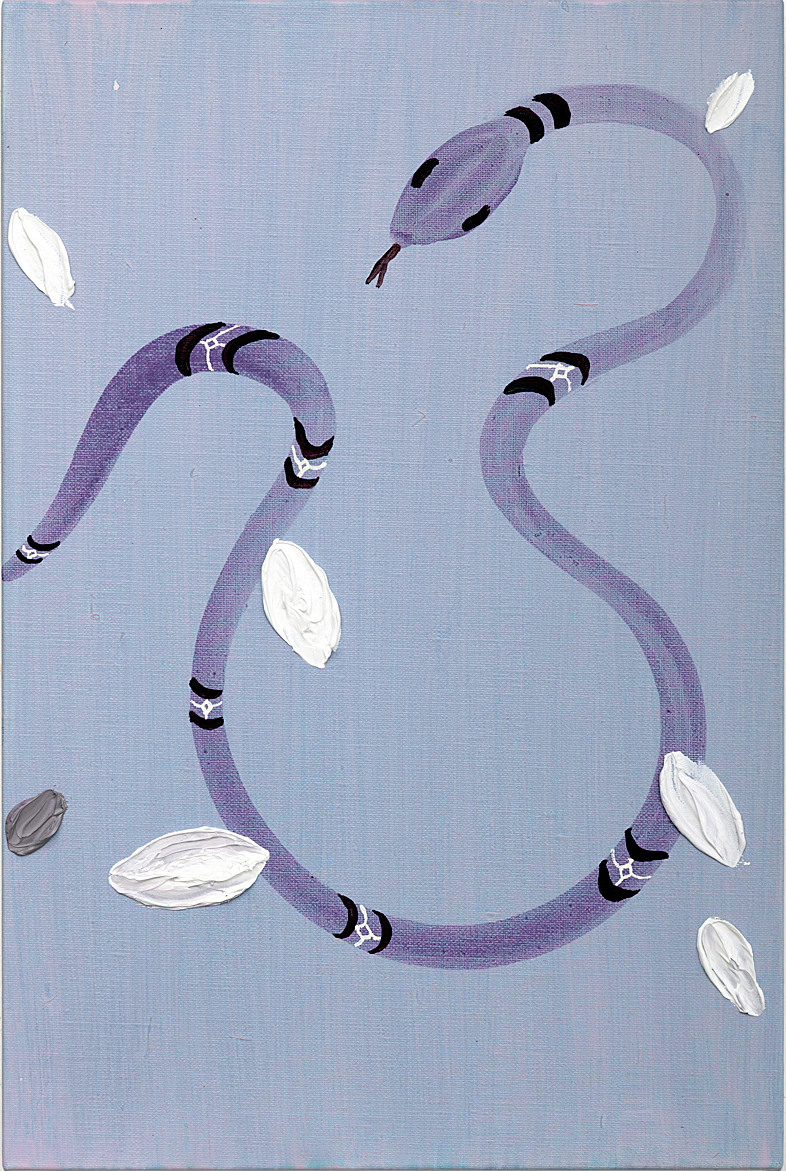

Still other paintings in this series suggest a process of redemption, a transformation from birth to death and vice versa, creating a kind of endless circle of emotional complexity, and psychological density. Lizotte utilizes images that have mythic associations. The snake, shedding its skin, becomes a talisman for grief and rebirth, but Lizotte breaks up the image into a series of smaller tableaux wherein the body of the snake spans a greater distance, its physical body literally fractured. The snake is a loaded subject and has a deeper connotative meaning that derives from both religion and mythology simultaneously. Lizotte’s snakes, however, are less menacing than they are transformative. She paints them more as symbols than literal beings, and for this reason the landscapes she creates, from painting to painting or panel to panel, generate a palpable sense of calm, a quietude that resonates throughout all of her work. Once again, the colors she has chosen for these panels are also calming and serene, and suggest that the creatures she depicts derive from the earth, and are drawn back into it.

In other images, the snake appears to float in front of a translucent curtain, which could symbolize loss, or something more sinister, or it could simply be a reference to the weight of the past, the burdens of loss and the challenges that come with living a life in the modern world. Again, the snake spans the entire length of the canvas, seemingly weightless, in strange opposition to the curtains behind them. Lizotte has painted the snakes as less serpent-like and more as an image that suggests the transformative powers of nature. In one painting in particular, the idea of transformation is keenly felt as a snake appears to be attached or devouring the tail of another.

Lizotte's use of color, and the impasto-like application of the medium itself, along with her understanding of space and form, is also very seductive. The thickness of the paint seems to mirror the deeper hidden content of the paintings themselves as though we as viewers must continue delving into the fractured narratives. For example, in another work, a starkly enigmatic face appears from out of the surrounding darkness. A few simple lines delineate a woman's anguished face. As with other images, a central figure occupies the middle ground of the painting, the surrounding landscape again a torrent of inscrutable blooms. Lizotte repeats a series of visual motifs again and again to great effect, and each appears to symbolize some aspect of loss, love and the passage of time.

It is true that in Lizotte's paintings, “the violets in the mountains have broken the rocks,” but I would take this a step further to say that the violets in the mountains have forsaken the rocks for a wider expanse of terrain, a broader landscape in which to grow and thrive. Each of the works in this exhibition commemorate loss as a means of transformation and rebirth, a celebration of the past, the present and the future simultaneously. We long to know the stories that inform the work, but more importantly, these paintings implicate us in our own stories, our own longings, our own itinerant hopes and desires.

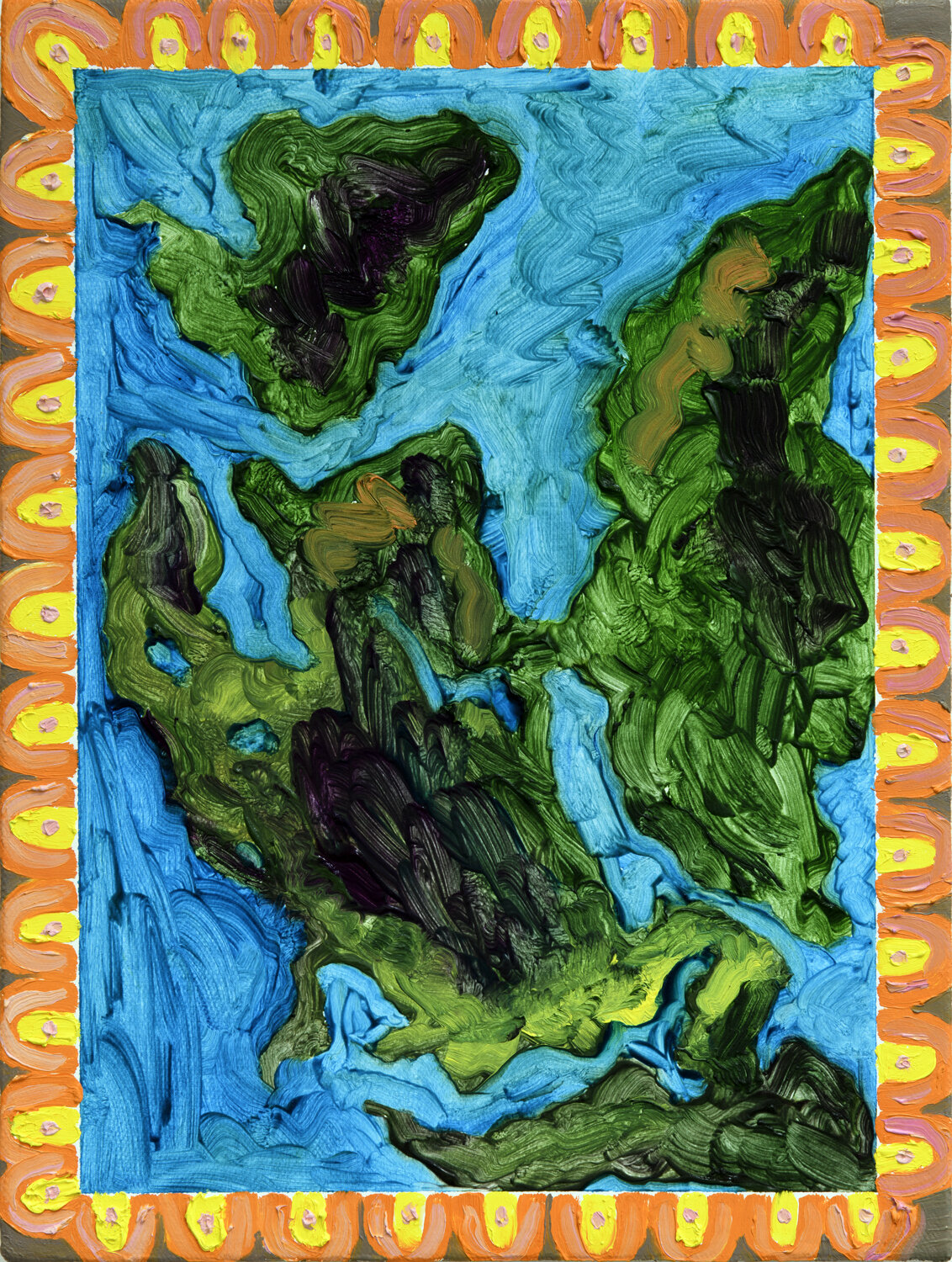

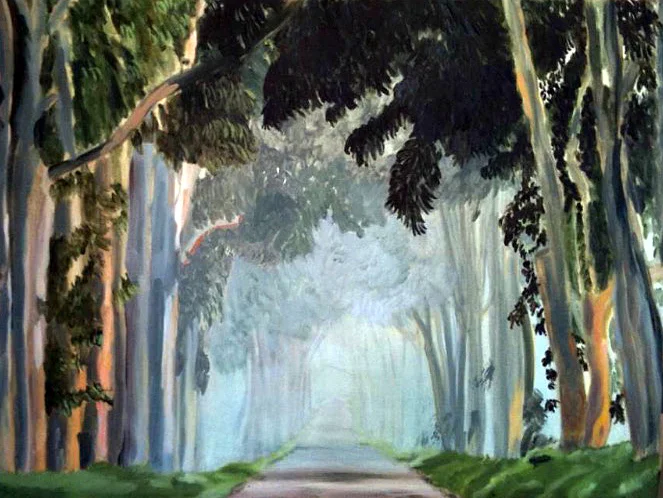

Gallery Landscapes

Gallery Landscapes

THE FOOL’S JOURNEY | QUARANTA | SPRING MAPS | THE LOS ANGELES SERIES | LOST PATTERNS | MERCURY | UNTITLED SERIES | LANDSCAPES | FLOWERS, ALWAYS

Please contact us if you’d like to view the complete collection.

Flowers, Always

Flowers, Always

THE FOOL’S JOURNEY | QUARANTA | SPRING MAPS | THE LOS ANGELES SERIES | LOST PATTERNS | MERCURY | UNTITLED SERIES | LANDSCAPES | FLOWERS, ALWAYS

Claude Monet said it best “I must have flowers, always, and always.” I too love flowers, and feel the exquisite beauty of flowers in bloom is timeless. The circle of life in the bloom of a rose is still ever fresh. As the globe has navigated through the despair of the Covid pandemic for the last two years I needed beauty and hope to bring meaning to life. I hope the viewer feels their own emotional connection to these flower paintings.

— Susan Lizotte