THE FOOL’S JOURNEY | QUARANTA | SPRING MAPS | THE LOS ANGELES SERIES | LOST PATTERNS | MERCURY | UNTITLED SERIES | LANDSCAPES | FLOWERS, ALWAYS

“The seasons and the passing of time resonated for me to represent the cyclical nature of birth, life and death. Fragility, vulnerability and strength in the midst of overwhelming emotional turmoil are elements to celebrate.”

— Susan Lizotte

Please contact us if you’d like to view the complete collection.

A Serene and Ghostly Presence: The Quietly Enigmatic Paintings of Susan Lizotte

by Eve Wood

Tennessee Williams said in his famous play Camino Real that “the violets in the mountains have broken the rocks,” meaning that something fragile and delicate can overtake even the harshest conditions, or soften the hardest heart. Susan Lizotte's painting's, mostly oil on canvas and wood, comprise a set of images that deal, both directly or indirectly with issues of mortality, love and loss.

Lizotte's adopted father passed in 2017 and these paintings are a visual response to loss, and are at once bold, lush and expressive in the very best sense of the word. They utilize flowers as symbols of loss but also as emblems of regeneration and rebirth. Artists like Marc Chagall and Wassily Kandinsky come to mind as these artists all utilize motifs of flowers and bright expansive fields of color to represent a larger more complex system of loss that ultimately includes love, forgiveness and celebration. As with these artists, Lizotte's work is also imbued with a sense of mystery and the fact all of the paintings are untitled adds to the sense of the miraculous having already happened, yet still continuing to blossom. They also are suggestive of a variety of literary references, not only Williams but the image of the wayward soul of Shakespeare's Ophelia comes to mind:

Her clothes spread wide;

And, mermaid-like, awhile they bore her up:

Which time she chanted snatches of old tunes;

As one incapable of her own distress,

Or like a creature native and indued

Unto that element: but long it could not be

Till that her garments, heavy with her drink,

Pull'd the poor wretch from her melodious buy

To muddy death.

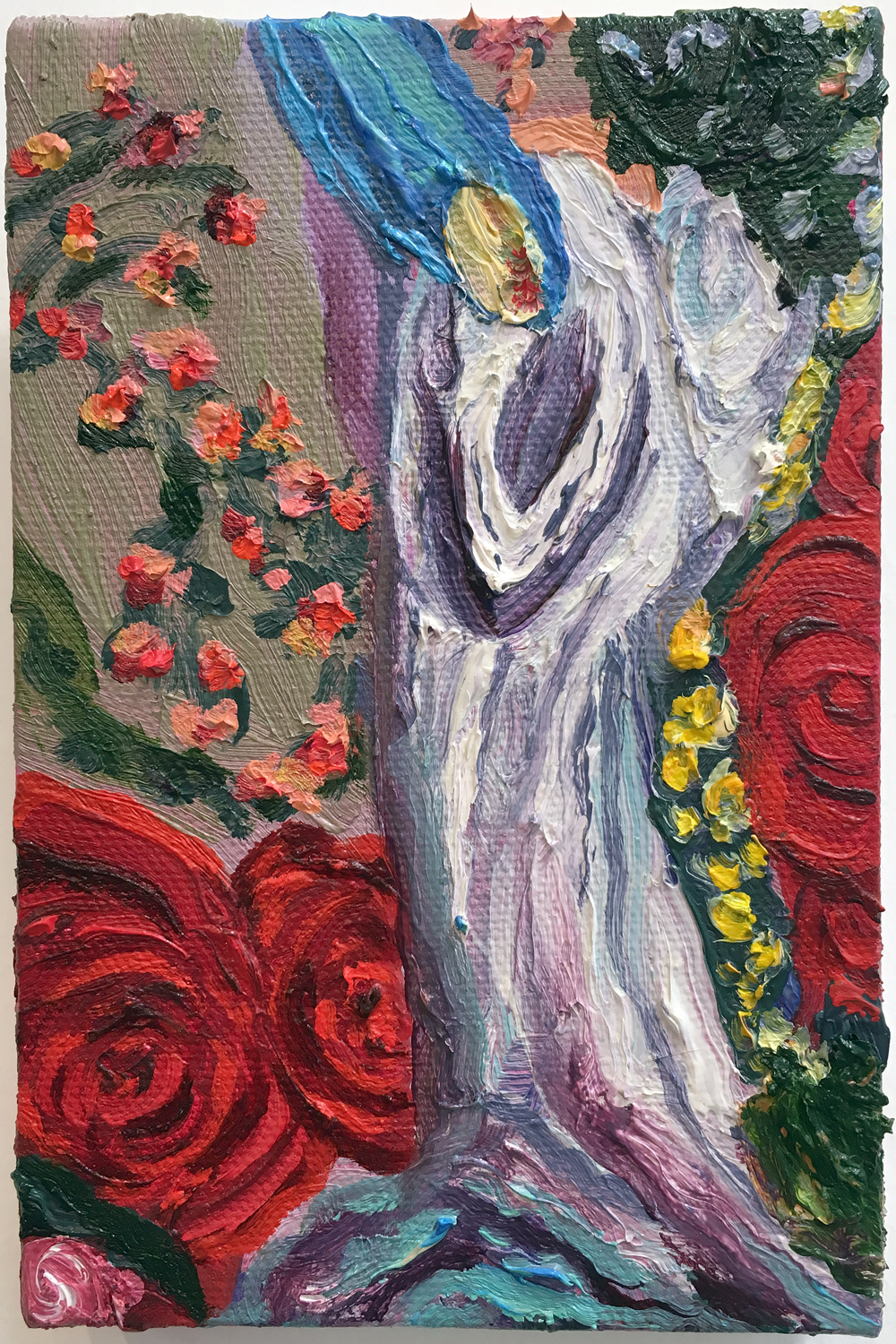

The fragments of disassociative images in Lizotte's paintings all suggest the female body, or parts of it seen at various intervals much like Ophelia sinking slowly into her watery grave, her body surrounded by the flowers she picked with her own hands. Though most of the paintings contain iconographic references to flowers, the images also contain more personal references as in one painting where a woman's dress appears to be floating in a vaguely disquieting field of poppies. Again, this is reminiscent of Ophelia, the dress with its ghostly presence, as a milky confluence of blues, grays and pinks dominate the center of the image, yet strangely, the dress is empty, or rather filled with the weight of possibility, fluid and changing, a hopefullness, a means by which the experience of tragedy, of loss might be transformed into a more positive association. The flowers in this image also reflect movement, a garland of blooms skirting the dress as though lifting it up and onto the wind. Giant blood red poppies punctuate the surrounding space, in a kind of menacing gesture that seems to balance the quietude of the floating dress.

These paintings are as much about what is not there as they are about what is keenly felt and experienced. Nowhere is this more apparent than in the loosely enigmatic image of what appears to be an arm or a leg, again seen to be floating disembodied through space. The appendage is covered ironically with a sheer fabric that could be a piece from a wedding dress or a wayward bit of lace. This sense of the unseen being seen and experienced by both the viewer and the artist together is also another underlying theme in the show, and again, as in other images from Lizotte's series, the central figure is surrounded on all sides by flowers; yet the painting is strangely interrupted by an encroaching black mass which could be representative of the weight of the past, unresolved memories or feelings yet to come. If one were to read this work metaphorically, you could argue that the painting is divided between two poles of experience, the burgeoning light and color on the left hand side of the canvas versus the complete absorption and negation of experience on the right.

This tentative balance between opposites– color versus no color, light versus dark, implied narrative versus complete abstraction is what makes these paintings powerful and engaging. Also, each of the works has a central image that is mostly recognizable whether it be a dress, a sleeve or a darkly shrouded encroaching mass of darkness that keeps us continually engaged as viewers. It's a discernible tension that exists within each of these images separately yet also operates on a larger scale collectively as an overall theme of opposition. Lizotte's narratives are not easily discerned, but are hard won like all good things. They keep us invested and looking deeper.

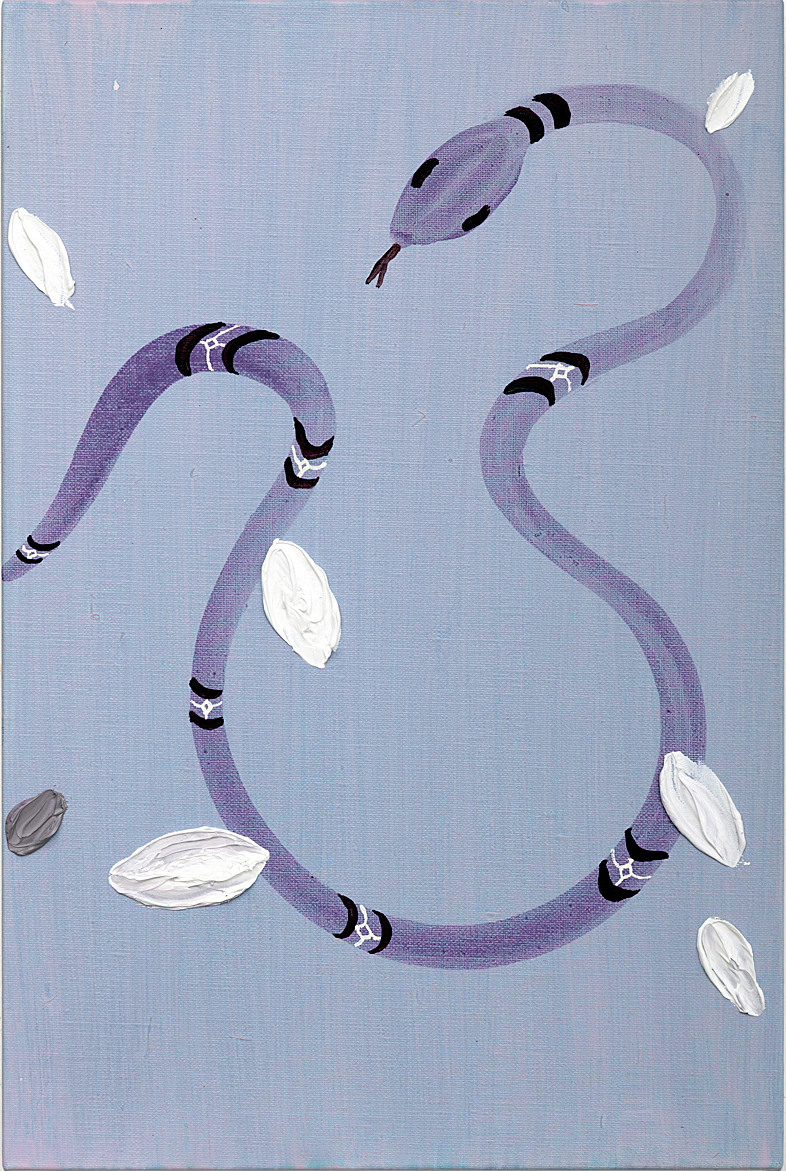

Still other paintings in this series suggest a process of redemption, a transformation from birth to death and vice versa, creating a kind of endless circle of emotional complexity, and psychological density. Lizotte utilizes images that have mythic associations. The snake, shedding its skin, becomes a talisman for grief and rebirth, but Lizotte breaks up the image into a series of smaller tableaux wherein the body of the snake spans a greater distance, its physical body literally fractured. The snake is a loaded subject and has a deeper connotative meaning that derives from both religion and mythology simultaneously. Lizotte’s snakes, however, are less menacing than they are transformative. She paints them more as symbols than literal beings, and for this reason the landscapes she creates, from painting to painting or panel to panel, generate a palpable sense of calm, a quietude that resonates throughout all of her work. Once again, the colors she has chosen for these panels are also calming and serene, and suggest that the creatures she depicts derive from the earth, and are drawn back into it.

In other images, the snake appears to float in front of a translucent curtain, which could symbolize loss, or something more sinister, or it could simply be a reference to the weight of the past, the burdens of loss and the challenges that come with living a life in the modern world. Again, the snake spans the entire length of the canvas, seemingly weightless, in strange opposition to the curtains behind them. Lizotte has painted the snakes as less serpent-like and more as an image that suggests the transformative powers of nature. In one painting in particular, the idea of transformation is keenly felt as a snake appears to be attached or devouring the tail of another.

Lizotte's use of color, and the impasto-like application of the medium itself, along with her understanding of space and form, is also very seductive. The thickness of the paint seems to mirror the deeper hidden content of the paintings themselves as though we as viewers must continue delving into the fractured narratives. For example, in another work, a starkly enigmatic face appears from out of the surrounding darkness. A few simple lines delineate a woman's anguished face. As with other images, a central figure occupies the middle ground of the painting, the surrounding landscape again a torrent of inscrutable blooms. Lizotte repeats a series of visual motifs again and again to great effect, and each appears to symbolize some aspect of loss, love and the passage of time.

It is true that in Lizotte's paintings, “the violets in the mountains have broken the rocks,” but I would take this a step further to say that the violets in the mountains have forsaken the rocks for a wider expanse of terrain, a broader landscape in which to grow and thrive. Each of the works in this exhibition commemorate loss as a means of transformation and rebirth, a celebration of the past, the present and the future simultaneously. We long to know the stories that inform the work, but more importantly, these paintings implicate us in our own stories, our own longings, our own itinerant hopes and desires.